Structural Racism & Drug Policy in the United States

Persistent Criminalization and Structural Racism in US Drug Policy: The Case of Overdose Good Samaritan Laws

An in-depth analysis of drug policy in the United States and the impact they have on marginalized communities.

Introduction

In the United States, the increasing prevalence of illicit substances and drug-related healthcare concerns have had a major impact on American drug policy. The case study carried out by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) focuses on public health oriented policy changes and how they are being undercut by the broader aura of perpetual and historic racist drug criminalization agendas.

Background

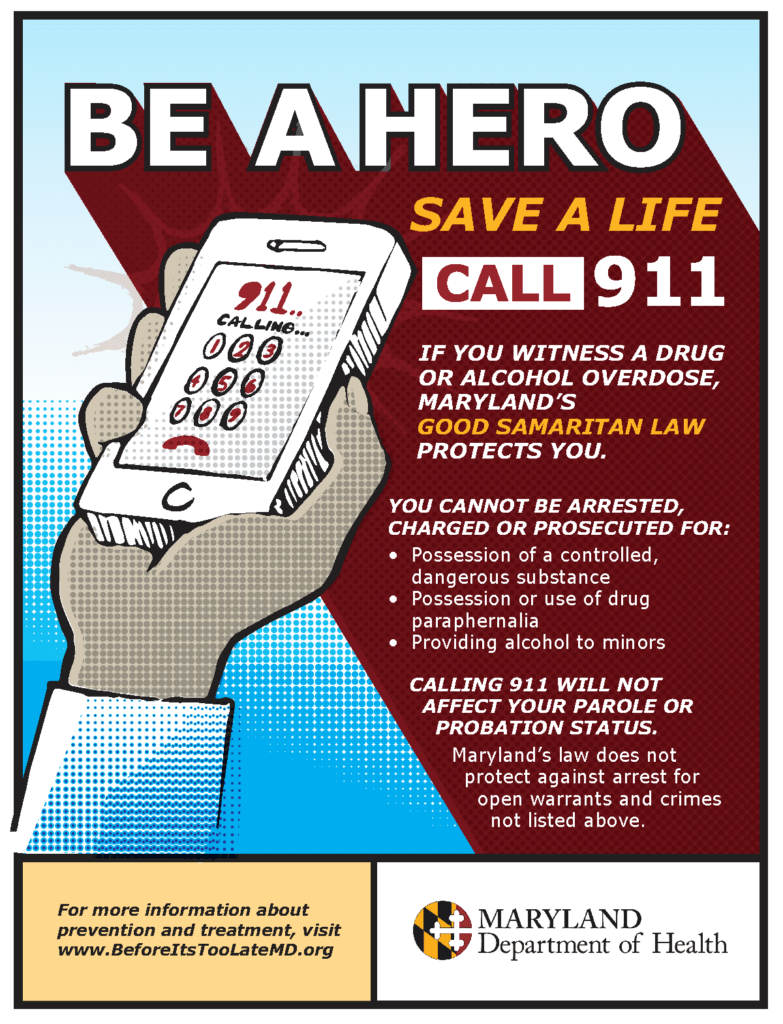

The Good Samaritan Laws (GSLs) are policies in place that encourage drug overdose witnesses to seek help by providing them limited legal protections from being prosecuted under illicit substance ordinances.

Challenges

Like any policy, there are obstacles to its efficiency, and outlined are three of the most significant barriers to maximizing the benefit of the GSLs:

1) Provision of legal protections – A lack of information and clarity about the protections that GSLs provide complicates help-seeking decisions during a critical window of time at an overdose that negatively affects the efficacy of GSLs among Black and Latino American communities. Issues like defining the term “arrest”, inadequate information about specific individual legal protections, and a general lack of accurate guidance about GSLs discourage overdose witnesses from contacting emergency services due to feelings of uncertainty towards GSL provisions.

2) GSL implementation and application subject to police discretion – GSL effectiveness therefore may rely on the level of entrenched racist policing culture + community’s perception on whether that culture has changed. In the United States, 20/48 active GSLs allow police to detain help-seekers even though they are protected from charge or prosecution. Preserving the ability to arrest and detain help-seeking individuals is unlikely to sufficiently dismantle fear of police as a barrier to medical help-seeking and has numerous downstream risks, even if charges are not pursued. This increases potential for stigma, harassment, and violence associated with police interactions for Black and Latino Americans within the communities that GSLs are meant to benefit.

3) Passing of further competing, legislation that criminalizes illicit drug users – In states with GSLs and drug homicide laws, witnesses in possession of drugs may be protected from legal consequences but if the overdose is fatal, they may face felony charges. Concomitant drug-induced homicide laws—along with laws that prohibit trespassing, loitering, possession with intent to distribute, and numerous other offenses of which people who use illicit drugs are frequently accused contribute to lower efficacy of GSLs and diminish the value of these policies to the communities they are meant to benefit. Structurally racist drug criminalization policies disproportionately limit the efficacy of public health oriented policy changes, given that Black and Latino Americans are getting charged disproportionately more with drug homicide charges.

Solutions

The persistence of a broader, structurally racist environment of criminalization that is maintained by policymakers and law enforcement continues to threaten health and racial equity outcomes. The analysis of the major barriers to GSL efficacy leads us to three recommendations for increasing the positive community impact of GSLs:

1) Ensuring that GSL legal protections are rule rather than exception (comprehensive protections)

2) Interventions to establish harm-reduction and public-health oriented environments

3) More direct and comprehensive approach to reducing drug-related harm that focuses on the health, rights, and dignity of people who use drugs

Impact

These drug and community health policies such as GSLs are hurting global development by furthering systemic racism and policy inequality for Black and Latino Americans. Without restructuring, the current drug policy system in America creates a social obstacle for furthering health interventions and improving the quality of life for all. The United Nation Sustainable Development Goals of “Reduced Inequalities” and “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions” are most relevant to this study due to the fact that inequality is still prevalent for these specific communities and that justice has not achieved for those being afflicted by disproportionate drug policy. Improving GSL and American drug policy means improving ways to hold higher law-making institutions accountable.

Lessons Learned

The largest focus of this case study is the application of the Values of Worthwhile Development. The value of Responsibility is most relevant to this study because it places emphasis on the responsibility that is involved with making GSLs effective, not just the general wellbeing of those that GSLs are targeted towards. Evaluating the responsibility of the police in their application of GSLs and their contributions to entrenched racist policing improves progress by defining internal obstacles to positive development. It is critical to also analyze and outline the responsibility of the government and policy-making bodies in ensuring that competing laws supplement rather than hindering GSLs. Lastly, ensuring that those in power understand their responsibility to make information about GSLs more well-known and accessible is important to establishing a more equitable and sound community.

Responsibility ensures that public health policy changes are working and benefiting the target population. Responsibility ensures that systems and cultures of racism in policing and legislation do not continue or increase as a result of GSLs. Drug and health policy should be actively benefitting rather than disproportionately targeting the communities that they are in place for.

Reference

Pamplin, J. R., 2nd, Rouhani, S., Davis, C. S., King, C., & Townsend, T. N. (2023). Persistent Criminalization and Structural Racism in US Drug Policy: The Case of Overdose Good Samaritan Laws. American journal of public health, 113(S1), S43–S48. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307037